Submission Deadline

28 February 2026

Judging

Date

24 & 25 March 2026

Winners Announcement

22 April 2026

28 February 2026

24 & 25 March 2026

22 April 2026

In the world of spirits, there are artisans whose dedication and passion transform raw ingredients into liquid art. One such master craftsman is Chip Tate, whose journey from a fervent bread baker to a distinguished distiller has been nothing short of extraordinary. In this exploration, we delve into Tate’s unique path, blending science, artistry, and a profound love for the craft, culminating in the creation of exquisite spirits. Join us as we uncover the story of a man whose expertise and unwavering commitment have left an indelible mark on the world of distilling.

I found my way to distilling in a roundabout way. In my youth, I was an avid cook and baker, specializing in particular in naturally fermented, hearth-baked breads. I've always had a fascination with yeast and its near-magical effects on grain. I would spend hours every day in the kitchen practicing the same recipes and striving for perfection.

But by the time I was in college, my attention turned towards beer and brewing. As a certified STEM geek coming out of high school, I decided to study theoretical physics initially but switched to philosophy and religion halfway through graduating with an undergraduate in Philosophy. I went on to earn a Masters of Divinity degree and nearly completed a Masters in Education before my plans changed. However, throughout my college and graduate school years, my true passion was brewing. Undoubtedly, I spent at least as much time studying brewing as I did my formal studies. I acquired every brewing book in English I could get my hands on and even a few besides in German when I had an opportunity to do a graduate fellowship in Switzerland in 1998-99.

After completing graduate school, I finally conceded that my true vocational passion was brewing and set out to become a brewer. While supporting my then-spouse at the time, I studied independently for the Institute of Brewing's diploma course in brewing. However, as a matter of coincidence, the Institute of Brewing combined with the Guild of Distillers to become the Institute of Brewing and Distilling in 2002, the year I sat for the exam, which meant that there would be a distilling section on the exam. After I recovered from my initial state of panic about there being new and unplanned material on my upcoming test, I came to realize that the Distilling section was largely comprised of engineering topics. As I had spent 4 summers and vacations working for a nuclear engineering company as part of a small high school scholarship, basic engineering topics were familiar to me. So, in 2002 successfully completed the IBD diploma exam in brewing and distilling.

Image Source: Chip Tate, curious about how we shape the copper

At the time, I was still resolved to apply this knowledge to the professional brewing of beer alone. But there is no doubt that the inclusion of that distilling section on the exam planted the seed of an idea in my head about distilling. Over the next 6 years, while working in academia as an assistant dean, I became more and more of a whisky drinker before making the jump to found Balcones Distilling in 2008. It was then that my trial by fire began. I and a small group of guys rebuilt an old welding shop into a small distillery making most of the equipment we used ourselves. It was during this time that I began building stills and related distillation equipment out of financial necessity.

Then in 2014, when I exited Balcones, I took that experience and skill set to build Tate & Company here in Waco as well. It was in that context that Tate Craft Copperworks was founded as well, which is largely focused on the equipment needed for Tate & Co., but we have also taken on a few third-party projects as well. We've made both steam-heated and direct-fired stills, less usual these days, ranging from 600 to 3000 gallons in charge capacity.

Image Source: Chip Tate, the stillmaker.

As president and head distiller, my days vary tremendously. I spend as much time in the administration of the business as I do either making stills or using them, but I always enjoy my blending work with spirits the most. Blending spirits is certainly hard work, as it can really exhaust both mind and body to nose and taste so many spirit samples over hours, but it is tremendously rewarding to be able to compose something beautiful from many spirit expressions into a well-orchestrated symphony so much greater than the sum of its parts.

It was really my early work in brewing that eventually brought me to distilling. It was the love I developed for the process of transforming grains into complex flavors and aromas through brewing that led me to distilling. Distilling is an extension of the same skills and processes used in brewing, with the added dimensions of distillation and maturation, which has always intrigued me. The complexity and integration of flavor that can be brought to bear on the final product by layering different effects together throughout the process fascinates me.

There are many areas of expertise a distiller must possess to be truly capable, but the most important is his or her ability to understand, keep track of, and evaluate the effect of many factors over long periods of time. Distilling aged spirits takes years for the final product to emerge. Above all else, a distiller must be able to keep track of all the decisions made from the mash tun to the cellar to be able to anticipate what will come of all of it years after the initial steps in production take place. Without this complex understanding of the process over time, it is impossible to consistently anticipate what will be produced in the glass.

Image Source: Tatedistillery (Instagram Page)

Absolutely. In my experience, there is no better driver of market interest in a spirit than the love that the maker brings to the tasting table. The best distillers can not only make great spirits but also inspire sales staff and the public alike through their knowledge, passion, and love for the spirits they make. There are few things born of love in the marketplace today, but most of us are looking for them all the same. The passion and investment of the artist who pours himself into a bottle every day is contagious and can have a dramatic effect on product marketing if done well.

A good distiller not only has the technical skills to understand and accomplish the production of good spirits but also the ability to aggregate that data over time to learn lessons and grow as a distiller.

The hardest part of being a distiller is having to balance the many practical and business components of the job along with the creative and artistic roles as well. The most successful distillers must operate both as practical entrepreneurs, with the many practical and operational demands that attach to the role, as well as a creative who can conceive and execute the artistic aspects of the role, often at the same time.

I tend to create spirits that have a story or a concept behind them, so I start there. A corn whisky focused on the basic flavors of roasted corn, for instance. In my experience, the best bartenders are just as passionate about great spirits as their makers, so the connection comes very naturally. I just try to start with a basic understanding of who I'm talking to, and what excites them about spirits, and go from there in an organic way.

One of the hardest things about distilling is that it is an expensive, long-term enterprise requiring consistency of vision and commitment in a business world that often struggles with long-term commitment and whose goals change often. One of the hardest aspects of making great spirits in the current climate is finding the right partners who share a similar long-term commitment to excellence and who understand long-term value to be the key to success not antithetical to it.

For me, a good life centers around family and satisfying work. Sharing quality time with my wife and children full of laughter and music while having the chance to do meaningful and fulfilling work professionally is essential to a good life.

It's hard to beat a nice dram of whisky enjoyed sitting on my front porch out in the countryside. The peace of the place makes it that much easier to fully appreciate a worthy whisky.

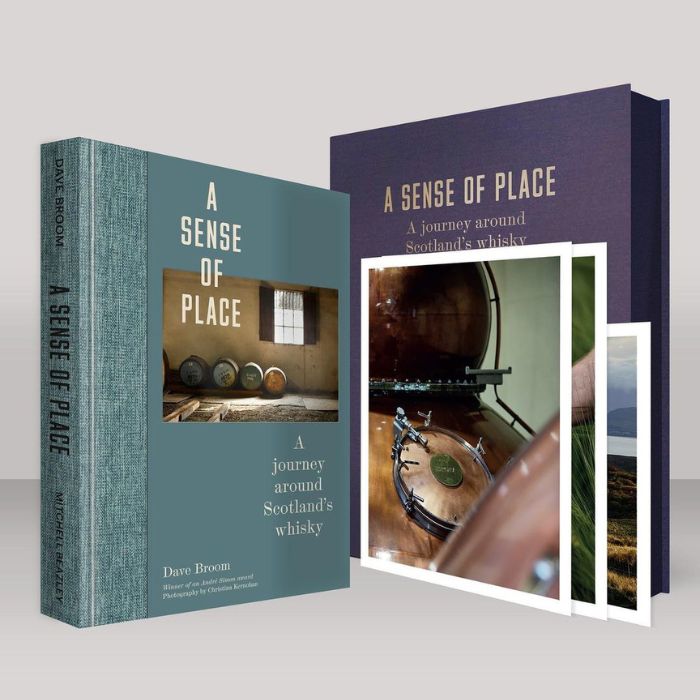

I'm a big fan of Dave Broom and his "A Sense of Place: A Journey Around Scotland's Whisky" as well as his book "Rum" are favorites of mine. Also, it's a somewhat technical work, but I think "Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing" by Graham Stewart and Inge Russell is an excellent work as well.

Image Source: Dave Broom (Instagram Page)

We do not currently source bulk spirits, but were we to do so, the same basic principles of spirit selection apply as they would for one's own spirits. Consistency, quality, and interest in character are qualities that any supplier needs to ensure in his or her products, regardless of market, including for bulk products.

First, I evaluate all the samples in front of me to see if any should be excluded because of certain faults or characteristics that I know would serve the blend. Oftentimes, I use this opportunity to consider if any of the barrels in question should be moved to another cooperage to help them mature better and in a direction more consistent with my goals. From that point, I often compose spirits the way one composes music. There are usually certain bass, mid-range, and tremble components that are desired in a blend, so I will then further select barrels that best exemplify each of those desired traits. Then the process of proper composition can begin and I will nose and arrange glasses spatially on the table which helps me track what I'm hoping to get from each sample and each group of samples in the blend. Finally, I will make preliminary blends of various groupings of the selected samples and let them meld together for a few hours. Then I will come back and make final decisions about which to include in which blend based on the outcomes of those preliminary blends. Once I have determined what I think I want in the final blend, I will make the blend up and let it rest overnight. The next day, with a rested palate, I compare that blend to several previous blends I have done, as well as other whiskies sometimes, and make a final decision to keep the blend 'as is' or to amend it.

Image Source: Chip Tate - checking on best-kept-secret collaboration brandy in-barrel up in Denison, TX.

I think yeast and fermentation can play an especially critical role in the complexity and quality of a spirit. Careful attention to the amount of yeast growth encouraged by dissolved wort oxygen, temperature, and even the use of multiple yeast strains all play a key role in not only ensuring the quality of the resulting spirit but especially in the complexity of esters created which play an important indirect role in which esters end up in the final mature spirit. Furthermore, the mistreatment of yeast and fermentation is one of the major causes of overly hot, soapy, and unpleasant spirits.

[[relatedPurchasesItems-63]]

I think the current trend of acquisition and consolidation of many craft distilleries is likely to continue. Growing even an already successful distillery is an expensive business that often requires third-party investment or acquisition. I anticipate this will remain true and lead to most would-be successful brands making alliances with larger partners for future growth.

Show your spirits where it matters. Get your products tasted by top bartenders, buyers and experts at the London Competitions — enter now.